Eleven-year-old Adam Leach lives with his family on a sprawling piece of land in rural Crawford County, Arkansas. A pair of rocking chairs sits on the front porch, and white-tailed deer often lope across the yard on their way to the woods beyond. Adam loves the sight of their lithe bodies jumping fences as easily as if they were hopping from one stepping stone to the next.

The deer make the natural world look like a playground. It has not been the same for Adam, who for years lived with danger all around him. Diagnosed with epilepsy, even the simplest activities—walking or riding a bike, could be catastrophic if a seizure occurred. At the height of his illness, Adam had more than a thousand seizures a day, nearly every day. For context, in 2022, he had only nineteen seizure-free days and was in the hospital thirteen times.

“He was always at the mercy of the next attack,” his mother, Kelly Leach, says. “If he was only having them every two to three minutes, that was a good day.”

Nights were especially fraught since that’s when the grand mal seizures were likely to appear, the worst of the five types Adam had. Sleeping was also when he experienced ESES epilepsy, which Kelly describes as an electrical storm in the brain. In his waking hours, he wore a specialized helmet in case a seizure knocked him out cold, causing him to fall.

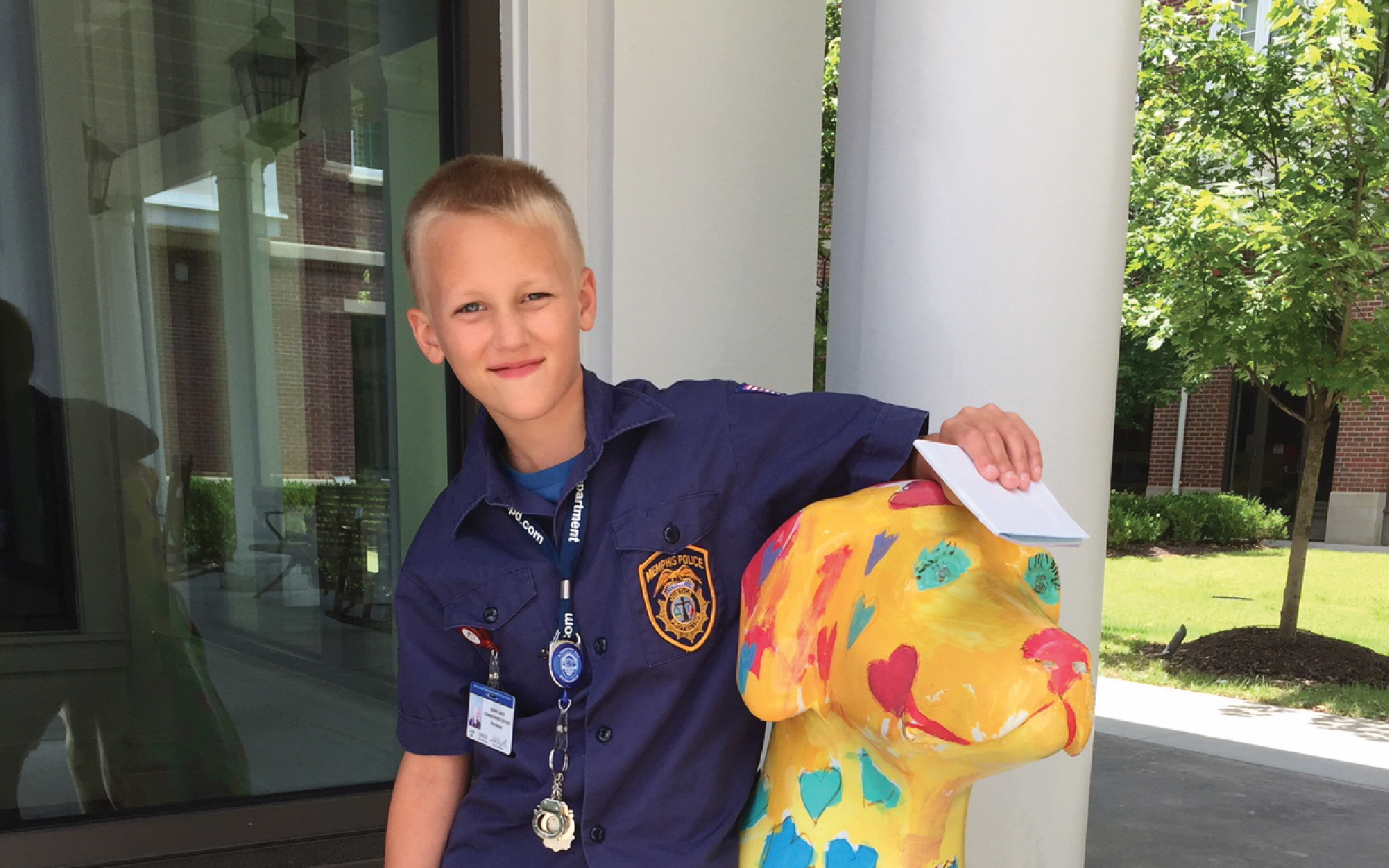

Today, Adam, his blond hair catching the afternoon sun, strides across the porch, his steps sure. He is at that precious point in boyhood: long-limbed, immensely curious, energy that seems boundless. Adam finds a thousand delights in his day, simple things like donuts, Smokey Bear, and collecting uniform patches from police and fire departments. His world has blossomed, after a surgery Kelly calls a miracle.

To be fair, Kelly believes Adam’s entire life is a miracle. She and her husband, Cliff, already with five children in their family, but wanting more, decided to have Kelly’s tubal ligation reversed. When they learned they were pregnant, they were overjoyed. The pregnancy went well until the thirty-fourth week.

“He’d stopped moving,” Kelly says, reflexively laying her palm on her stomach. “He loved music, and he didn’t respond to the music at church. I started thinking; I couldn’t remember him moving the day before.”

An emergency delivery took place on July 21, 2013. “He was crying when they handed him to me, and he seemed to be okay at first, but that quickly changed.” There were abnormalities with the umbilical cord, which Kelly says affected Adam’s nutrition, oxygen, and blood flow. “The doctor said it was a miracle he was born alive.”

On the fourth day in the NICU, Adam had a seizure. Further testing showed a Grade IV bleed on the right side of his brain. The experts warned of possible future complications, including loss of vision, intellectual impairment, or cerebral palsy.

“Sixteen days later, we brought him home, and he seemed like a typical baby, only smaller. For three months, he barely slept. I slept three hours a day for the first three months. Looking back, we know that he probably had things going on that we were not aware of.”

Already, Adam had a neurologist, and he seemed to stabilize. For years, there were no seizures. But on September 15, 2018, when Adam was five years old, that changed.

It was a sweltering day, and Adam had been playing outside with his older sister, Bryleigh. At two o’clock, the family drove to town for a late lunch, and on the way, Adam fell asleep, and Kelly had to wake him.

“He walked into the restaurant. We got in there, and he started tapping on the table with a fork, rhythmically. I took the fork away, and he continued with his fingers. He was looking at us but not talking. Just a dead stare. I took him outside to talk to him, and his head started jerking to one side. Then I knew; he was having a seizure.”

That seizure lasted forty-five minutes and changed the trajectory of the family’s life. A trip to a local hospital was the starting point. From there, Adam was examined at Arkansas Children’s Hospital.

About two weeks later, Adam had another forty-five-minute seizure. “That was the beginning of a horrific roller coaster.” Some of his seizures caused Adam to stop, stare, and flutter his eyelids. This lasted only seconds but happened all day long. Others were more severe.

“They told us he would likely outgrow it.” But that didn’t happen, and over the next four and a half years, Adam tried fourteen medications, none of which worked long-term.

For a long time, the phone rang regularly, with those who knew the family checking in. But the news was always the same. Adam wasn’t getting better. Kelly takes a breath and says, “People stopped calling.” Her voice wavers. “You become isolated… When people don’t know what to say or do, they stay away.

“We’ve had grown construction men up here working who left in tears. Adam would have drop attacks, where his body would just pull him down, and he would fall like a tree. We still counted our blessings. At the end of the day, Adam was still with us, and he was safe for another day.”

In Kelly’s hands, she holds a binder stuffed with notes and medical records, a testament to her quest to help Adam. She’d heard of Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis, and in October 2022, decided to seek their advice.

Le Bonheur has a ROSA One Brain robot that helps neurosurgeons pinpoint where a child’s seizures are located and what areas of the brain to avoid during surgery. The technology, called stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG), is minimally invasive and places tiny electrodes in the brain to collect critical information. The patient is then monitored for several days, and the information from the electrodes creates a map for the neurosurgeon to follow.

On February 23, 2023, Adam’s team, headed by Neurosurgeon, Dr Nir Shimony and Neurologist Dr Sarah Weatherspoon, was ready to go. By then, Adam was using sippy cups and a wheelchair. Dr. Shimony removed a cutie-orange-sized area of tissue from Adam’s brain. Oddly enough, it was located beneath a dark birthmark on the side of his skull, where his otherwise blond hair came in brown. It was as if Adam’s body was marking the spot where the trouble lay.

The surgery was a bigger success than anyone could have hoped for. His seizures didn’t lessen, they vanished. His cognition continues to improve. When they tested his eyes two months ago, his vision had gotten better, not worse.

It’s been twenty-two months since Adam’s family prayed for him to sail through surgery. Twenty-two months of wonderfully ordinary days. Every six months, he returns to Le Bonheur for testing.

Adam listens to his mother as she describes how much joy he brings to her life. He smiles that golden smile. He says he wants to be a police officer one day or maybe a firefighter, to help people in their time of trouble.

He looks across the yard for signs of deer with his sister, Bryleigh, beside him. Kelly smiles at her two children and sighs. The Lord is good, she says. She’s seen His work. His perfect work done in His perfect time. She has witnessed His miracle. A miracle named Adam.

3.4 million Americans are affected by epilepsy. For more information, visit the Epilepsy Foundation of America at epilepsy.com.

words MARLA CANTRELL // images KELLY LEACH