[title subtitle="words:Dwain Hebda images: Subiaco Abbey and Dwain Hebda"][/title]

The abbey bell sang its hearty summons shortly before mid-day, each peal beckoning, cajoling, compelling.

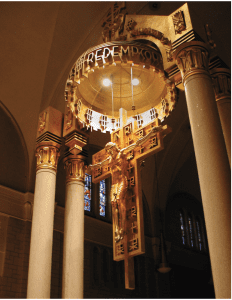

“You want to join us for noon prayer?” asked Brother Ephrem O’Bryan, OSB, brightly. His invitation accepted, Brother Ephrem shuffled out of his office for the short walk to the church sanctuary. The stroll winds through a meticulously kept courtyard of riotous floral color set against the stately stone abbey walls, a somber statue of St. Benedict at its center.

“St. Benedict used to face the other way,” said Brother Ephrem, poking a thumb to the abbey’s patriarch. The statue, which originally faced a north entrance to greet visitors, was turned south after a devastating fire in the 1920s left him staring at only rubble from which the abbey church eventually arose. “When we turned 100, we turned him back around so he could face the church.”

Subiaco Abbey, a Benedictine community in rural Logan County, Arkansas, is full of such wonderful details curated in the lives of the monks who live, work and pray here. Across its roughly 1,500 acres the abbey serves a variety of purposes: Catholic worship, a working farm and ranch, timber and sawmill, a retreat center, and a prestigious boarding school for boys.

Subiaco Abbey, a Benedictine community in rural Logan County, Arkansas, is full of such wonderful details curated in the lives of the monks who live, work and pray here. Across its roughly 1,500 acres the abbey serves a variety of purposes: Catholic worship, a working farm and ranch, timber and sawmill, a retreat center, and a prestigious boarding school for boys.

But it’s in the hearts and hands of the fifty-one men here that Subiaco Abbey and its guiding principle, the 1,500-year-old Rule of St. Benedict, are most clearly expressed. For many of them, the charism has unfolded over the bulk of their lifetime, for others, it’s just beginning. “What attracted me here was the community life,” said Prior, Brother Edward Fischesser. “I think that community is a big draw for some of the younger people, too. They’re looking for that. They come, and they want to dedicate themselves to something. It’s not just, ‘I want to have a room here,’ you know?”

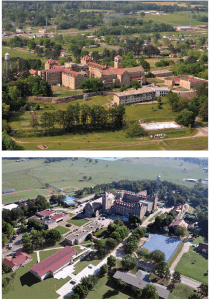

Subiaco Abbey is at once everything you envision and nothing you expect about a monastery. Perched on a hilltop near Paris, the imposing abbey building with its red rooftop shimmers in the Arkansas sun. Set against the emerald fertile valleys and heavily timbered foothills of the Ouachita Mountains, one’s first sight of the medieval-looking abbey is a dramatic experience. Every monk here has a story about greeting wide-eyed visitors who aren’t completely sure what they’ve just discovered. “People that go out on the weekends for a drive around beautiful Arkansas stumble across us,” said Brother Matthias Haggie, OSB. “My absolute favorite question I get is, ‘What is this place? Is this a prison?’

“There is a mindset that monasteries don’t exist anymore, and there’re a lot of non-Catholics that are not aware of the religious order side of the Catholic Church. I love giving tours of this place, giving our history. People are just fascinated at the idea that a monastery still exists in the United States, let alone Arkansas.”

The original abbey sat across the road at a ragged spot in the woods to which three pioneering Benedictine monks were dispatched from their Indiana home community in 1878. There, they laid the foundation for what was to stand for 139 years and counting. In time the crude log structures gave way to more refined buildings while the surrounding land was tilled for everything from corn to vegetable gardens to vineyards to fuel the monks’ pastoral work throughout the area.

In 1901 a fire started in the cookhouse adjoining the abbey, burning the original structure to the ground. By good fortune, a new stone abbey and academy were nearing completion, and the present-day facility was dedicated June 15, 1904. In 1927 the new structure also burned and, hampered by the economic malaise of the Great Depression, full recovery would not be realized for forty years.

Fire and finances haven’t been the only threats the community has faced over the decades. As the Center for Applied Research at Georgetown University reported in 2015, the number of men in religious communities has decreased sharply, from nearly 42,000 in 1970 to fewer than 18,000 a couple of years ago.

As an order the Benedictines fared better than most during this time, ranking second among the ten largest men’s religious institutions in the U.S. with 1,324 members and having decreased “only” forty-seven percent. Still, there were many years where new crosses in the abbey cemetery outnumbered new faces at the table.

Most of the forty-seven professed monks who live here now have seen the lean days up close – noontime devotion is permeated by bowed gray heads and folded weathered hands – but recently there’s been an uptick in new members, who spend more than four years in formation before taking their final vows as a full member of the community.

Most of the forty-seven professed monks who live here now have seen the lean days up close – noontime devotion is permeated by bowed gray heads and folded weathered hands – but recently there’s been an uptick in new members, who spend more than four years in formation before taking their final vows as a full member of the community.

Brother Raban Heyer, OSB, is one of the newcomers. At twenty-seven, he’s not the youngest one here, but he’s close. He said he chose a monastic life after years of searching other paths, including working as a parochial school teacher in Little Rock. “I think it’s the balance for me, coupled with the stability,” he said. “The balance between having a prayer life, having a work life and part of my work involves coaching track and cross country, so that helps me take care of myself physically. It’s very fulfilling to my whole person.”

“People who come here see we’re not that strange or weird, but in one sense, I guess we are,” said Brother Edward. “We’re pretty stable here. I mean, when you make your solemn vows, you can almost pick out your cemetery plot because you’re not supposed to be going anyplace. And that’s unusual today, that stability. People are so mobile.”

While not for everyone, the appeal of monastic existence isn’t hard to understand, nor is it irrelevant in the modern world. St. Benedict wrote his treatise for a righteous, fulfilling life after becoming convinced that society was going to hell in a handbasket and that was just under the Romans. Imagine what he’d think today.

Of course, Subiaco Abbey is still of this world which means having bills to pay. The community survives on donations, tuition for academy students seventh through twelfth grade and hosting various retreats. Also, many of the monks’ daily labors support the abbey’s various cottage industries. Its Monk Sauce (hot habanero sauce that is not to be taken lightly) and Abbey Brittle peanut brittle headline the community’s catalogue alongside calligraphy, handmade soaps, candles and carved items.

Brother Jude Schmitt, OSB, works every day in the wood shop, a skill he’s shown since childhood and his Ora et Labora here since the 1970s. The shop churns out a dizzying variety of plaques, clocks and other wooden items by special order or to sell in the abbey gift shop and online. He’s done altars and other sacramental furniture for churches down to hand-turned chess pieces.

Brother Jude Schmitt, OSB, works every day in the wood shop, a skill he’s shown since childhood and his Ora et Labora here since the 1970s. The shop churns out a dizzying variety of plaques, clocks and other wooden items by special order or to sell in the abbey gift shop and online. He’s done altars and other sacramental furniture for churches down to hand-turned chess pieces.

A recent donation of computer-driven equipment opened the door to a wide range of new products, including incredibly detailed etchings that, combined with his artist’s eye for color and finish, leap off the surface.

It’s quiet in the workshop except for the rhythmic trill of the bit on the face of the wood. Commingled sawdust yields its incense into the air. A man of few words, this is how Brother Jude likes it. “My favorite time to be in the workshop is on a rainy morning,” he said. “When I’m working, it clears my head of all other thoughts. I can just concentrate.”

There’s a tile in the floor of the abbey church, the Mary Marble, which features veining that outlines the Virgin Mary cradling a swaddled baby Jesus. It looks like any of the other hundreds of tiles, except when viewed from the particular angle of one’s head bowed in prayer from a spot in a front pew. Catholics hold a specific devotion to the Blessed Mother and her presence in the marble is comforting for the men who have planted their lives here, men who radiate their vocation to visitors from all walks of life.

There’s a tile in the floor of the abbey church, the Mary Marble, which features veining that outlines the Virgin Mary cradling a swaddled baby Jesus. It looks like any of the other hundreds of tiles, except when viewed from the particular angle of one’s head bowed in prayer from a spot in a front pew. Catholics hold a specific devotion to the Blessed Mother and her presence in the marble is comforting for the men who have planted their lives here, men who radiate their vocation to visitors from all walks of life.

“Many of our visitors come looking for some peace and quiet, to get away,” said Abbot Leonard Wangler, OSB. “They come to get someplace where they can just think. They’re looking for someplace they can get away and be by themselves and in their association with God.

“We’re providing for them a place where they can come and wind down for a few days. Oftentimes, we don’t realize we’re projecting an image for people. We’re not purposely projecting that image; we’re just doing what feels right to us and letting people see God at work in us.”

Abbey Facts

Visitors are welcome at Subiaco, in groups or individually. Join the monks for Mass, one of three daily prayer times or just walk the grounds. First-timers should start at Coury House to get a self-guided walking tour map which leads the visitors to the various points of interest.

The abbey credo “Ora et Labora” is Latin for “pray and work.”

Subiaco monks do observe periods of silence as part of their day, but this only happens at breakfast and at night. During “working hours” visitors may approach and talk to the monks.

Single Catholic men ages twenty to forty-five seeking a life in vocations are eligible to apply to become a brother. There’s also an affiliation for lay people, called oblates, which is connected to the Benedictines but they do not take vows or live in the monastery. Both men and women can become oblates.

Benedictines are traditionally associated with ravens. St. Benedict kept one as a pet and St. Meinrad, another key figure in Benedictine history, had two. Subiaco thus features a pair of the birds in its coat of arms.

Subiaco Academy

405 North Subiaco Avenue

Subiaco, Arkansas

479.934.1000

countrymonks.org

Subiaco Academy, located on the Abbey’s 1,800 acres, is one of the premier international boarding and day schools for young men in grades seven through twelve. The school maintains a 100% college and military acceptance rate amongst its graduates. Every school day, you can see young men from Fort Smith and the surrounding area boarding the school’s bus for a day of learning at the Academy. Often, this tradition is passed down through generations, so that all the men in the family have the Subiaco Academy experience.

To find out more, visit subiacoacademy.us.