Part I of Tommy’s Story, The Greatest American Hero Part I, appeared in our June, 2022 issue. You can find it here.

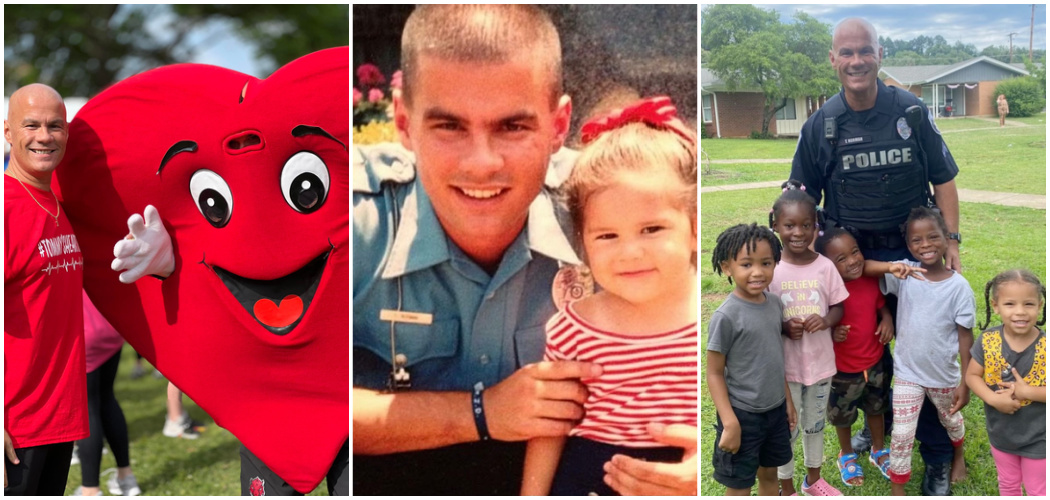

From the Heart: The Tommy Norman Story, Part II

Tommy Norman looks down at the piece of paper, weighs it in his hands. It’s an actual letter, the kind no one gets anymore.

“Dad, I miss you,” it began.

The letter was written last summer by Tommy’s daughter Alyssa, who was living at Harbor Home in Conway. Harbor Home calls itself a place for women “coming out of the darkness of addiction” and at that point in her life, that fit Alyssa like a glove. Drugs had landed the young mother in trouble, got her arrested a couple of times and, as drugs will, wrecked many of the more promising elements of her life, including her relationship with her dad.

“We didn’t talk for a while,” Tommy says. “I can say that it was me being prideful. I can say that it was the choices she made in life. But there were times in life that we would go six months, a year, and wouldn’t talk.”

The situation was complicated, even for Super Cop Tommy Norman, who’d gained international attention for his hands-on community policing. Through social media, millions saw Tommy interact with kids, show love to those who had received precious little of it, and preach hope to those who’d lost their way to the very beast with whom his daughter struggled.

None of that adulation and notoriety really mattered; no family is out of reach of the dragon, not even the man sending so much positivity into the universe. Through Alyssa, the poison cackled and sneered at him, and the light melted into darkness, which slapped him daily across the face.

And then with one letter from Alyssa, a door cracked open. “I can’t make any phone calls, but I can write letters,” it read. “We can have visitors on Sunday. They have a church service every Sunday afternoon.”

Tommy showed up the following weekend, embraced his daughter and they cried. From a rare place in their souls, they said how they’d missed one another, how much they loved one another. How they would make things right together. It felt like the last mile to home.

“It was just a beautiful, beautiful moment,” Tommy says. “She needed her dad, her dad needed her. As part of her recovery, having her dad back was huge. I don’t think I realized how huge it was.”

***

The reunion helped father and daughter bring back some of what time had cost them, time they both had had to share with Tommy’s career in law enforcement. It was a calling that had turned into a movement, dominating his time and giving him a measure of fame for his unique style of community policing.

It’s not that Tommy hadn’t always prized his children – he almost dropped out of the police academy because it kept him away from them – but from the day he started with the North Little Rock Police Department, his was a singular and lofty goal that he was unconditionally committed to upholding. “I was lucky to grow up in the Levy community of North Little Rock,” he says. “My mom was known for being nice to everyone and I learned to love people at a young age. White, Hispanic, Black, brown, I learned not to focus on color.

“When I graduated from the academy, I had different goals than others in law enforcement. I wanted to be able to help people, I wanted to meet people, I wanted to love people, I wanted to hug people.” This mission put Tommy into a class entirely by himself as a police officer. Every day, he got out of the cruiser and walked his assigned neighborhoods, trying to connect with people. At first, backs were turned, and blinds were drawn, but this didn’t stop him from chipping at the walls standing between the neighborhood and the police.

Of course, the uniform carries certain responsibilities and Tommy was committed to upholding the law. Over time, the goodwill he’d garnered let residents accept he was just doing his job, but it was an uneasy understanding at times, even from his peers.

“There’s been times I went to arrest people and as I’m taking them off to jail, I hear, ‘Hold on. You’re supposed to be the cool cop. You’re supposed to be the officer that everyone likes,’” he says. “I also got bagged on by some of my fellow officers for keeping an ice chest in the trunk of my police car. At the beginning of every shift, I would put cold drinks in there, Gatorade; I would keep peanut butter crackers and Pop Tarts and I’d hand them out. There were officers who didn’t agree with that type of approach, but I can tell you, there have been a lot of crimes solved from information forwarded to me because of peanut butter crackers and a cold drink and a visit on the front porch.”

Throughout his career, Tommy engaged people with an authenticity of spirit everyone could see. More than once a mother called to say her child had committed a crime and would surrender only to him. Once, a homeless man in Little Rock called into the NLR police station asking for him, a call that led Tommy to cross the river to meet, where the man confessed to murder. The man specifically wanted to surrender to him because of his positive reputation, a reputation that had now helped solve a homicide.

It was heavy stuff, especially with the media adulation he received. Tommy’s mother ensured he stayed grounded. “I’ve spoken all over the United States. I’ve been invited to the Grammys, the Dr. Phil show, and I’ll be honest, there’s been a few times I’ve gotten close to being sidetracked by all the attention,” he says. “But my mom taught me to stay humble. She would always say, ‘You may be at the top, doing great things, but there’s going to be people out there that want to bring you down.’”

***

That point came home to roost November 17, 2021, when Tommy’s phone buzzed. It was Harbor Home. Alyssa had overdosed the night before and just like that, she was gone.

“I just screamed and yelled. Luckily, I had two other officers with me because I started to collapse, and they lifted me up,” he said. “When I got to Conway, she was still in the bathroom and the coroner was already there. I waited until they carried her body out. I remember it was a white body bag.”

Tommy had spoken to Alyssa the night before and remembers thinking she sounded off. But she’d been doing so well that he chalked it up to fatigue after a long waitressing shift. Sometime after that, she relapsed, and it killed her.

“I asked the coroner, ‘Can I see my daughter?’ Well, I already knew the answer, because I’ve been a police officer for so long,” he says. “He put her in the back of the van and the van drives off. I can hear every piece of gravel the tires of the van are hitting.”

In the time since, Tommy has searched out the meaning in Alyssa’s life, refusing to let her twenty-six years be defined by the numbing senselessness of her death. There’s much there that shows even in her pitched fight for sobriety and soul, Alyssa never changed at the core of what she believed and had been taught about loving people. Rediscovering her faith, she was baptized and afterward hugged Tommy in a warm, enveloping sense of peace. During her recovery, she spoke candidly and publicly about her addiction in order to inspire others, rekindling her bright inner light to illuminate those still in the dark. These and many other moments combine to reveal the true fiber of her character, indelibly shaped by her dad’s example.

“She faced a lot of demons in life, but she never stopped being nice to people,” he says. “I don’t know what it’s like to be an addict, but from what she told me, going through withdrawal was like having the flu times ten. When you’re going through that, it’s easy to stop being nice, but she never did. She would always connect with the new girls at Harbor Home because she wanted to make them feel better.” Alyssa was a great, great woman. Everybody loved her. But she had a weak moment. And we all have weak moments, but Alyssa’s weak moment took her life. It was terrible. It was the worst day of my life.”

As easy as it is for him to celebrate his daughter, Tommy finds it just that hard to mourn her. For months now, he’s waited for the dam to break, to weep, but something in the universe won’t give him that. Instead, his broken heart masqueraded as a heart attack in March and no ordinary one at that. When his wife brought him to the emergency room it was discovered he had ninety-five percent blockage and required two stents. In other words, something most people don’t come back from.

“This is probably the most powerful thing I can say about it,” he says. “My wife, the medical personnel, my heart doctor and God all played a big role in this, but Alyssa Norman saved my life. Alyssa said, ‘Dad, not today. You’re not coming to see me today.’”

Having dodged the widow maker’s best punch didn’t go unnoticed, however. Tommy took stock of his health, started exercising and took off some weight. As he had done for everyone else, he was now doing for himself.

“Alyssa used to tell me, in the months leading up to her death, ‘Dad, just rest,’” he says. “Well, I’m pretty stubborn, but this heart attack that I had, I have started listening to that. My health is more important than anything. It’s more important than my job, it’s more important than what I do in the community.”

***

As we talk, Tommy is getting ready for his return to duty. He won’t do anything differently, he says, but nothing about his life or his vocation can be the same. From now on when he hugs a child, greets a neighbor or reaches out to the addicted and afflicted, he’s cloaked in a glowing light. Daddy’s girl is protecting him, holding him steady and uplifting others.

“It’s hard that Alyssa’s gone, but she’s saving lives today,” he says. “There’s a hashtag that went viral, ‘Do it for Alyssa.’ What does that mean exactly? Well, it doesn’t necessarily mean stop using drugs; it can mean smile at someone, it can mean say hello to someone, it could be give someone a hug, because Alyssa did all those things.”

“I don’t know what is waiting for me on the other side of this, but I do know it’s going to be something big. There’s a silver lining through Alyssa’s death in that it’s saving other addicts’ lives. The silver lining of my heart attack is using my story to raise awareness about heart disease. I feel like I have so much more to offer, so much more to give.”

If you or someone you know are struggling with drug addiction, there is help available. Please call any of these national hotlines for assistance in locating treatment programs in Arkansas.

National Council on Alcoholism & Drug Dependence Hopeline: 800.622.2255

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA): 800.622.HELP (4357)

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA): 800.662.HELP (4357) / 800.487.4889 (hearing impaired)

If you are experiencing the symptoms of a heart attack, call 911 immediately. For more information on heart health for you or a loved one, visit the American Heart Association website (heart.org).

**Follow Officer Tommy Norman at facebook.com/tommy.norman.35574 or on Instagram at tnorman23. Part I of Tommy’s story appeared in our June issue. You can find it online at DoSouthMagazine.com.