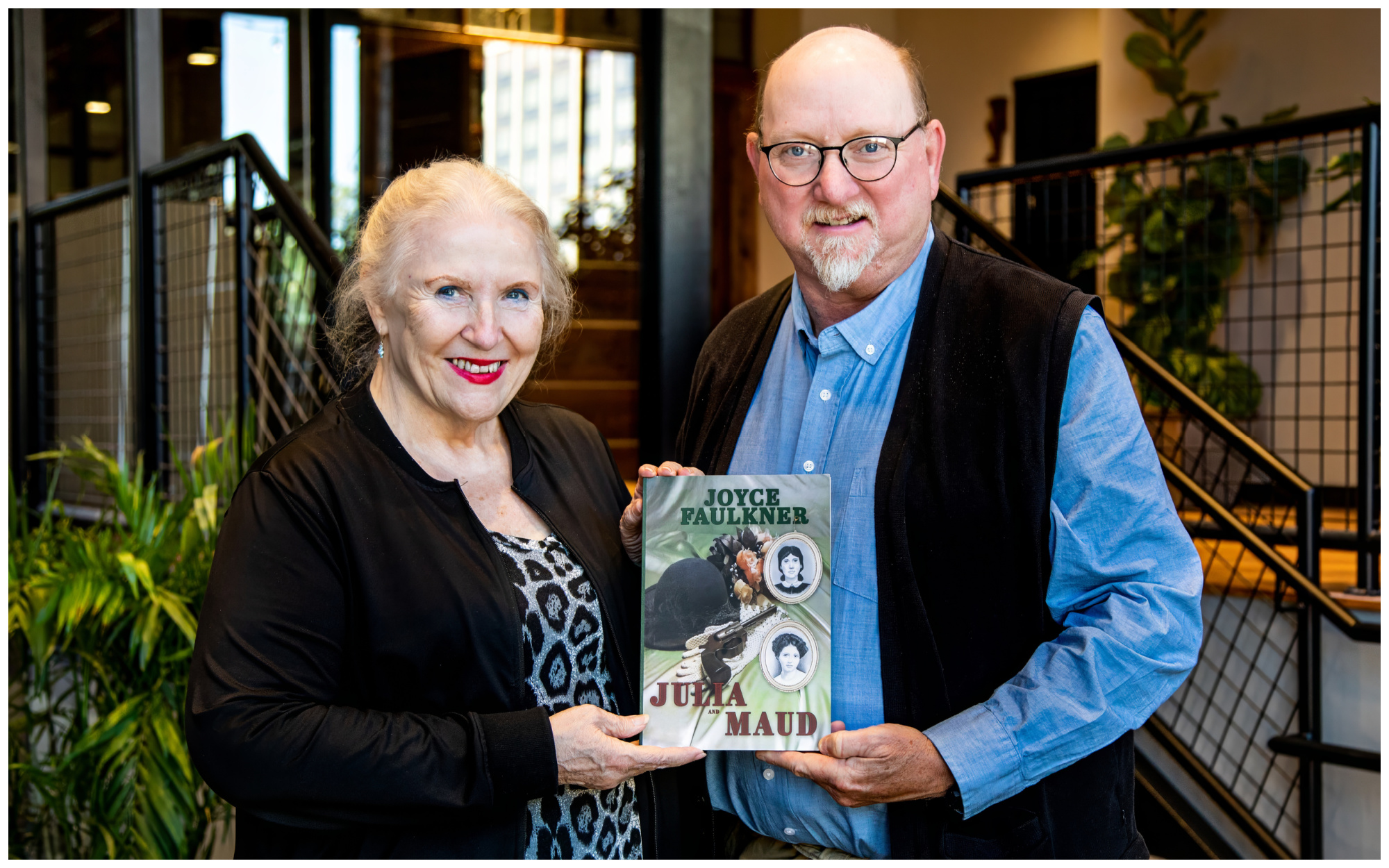

Fort Smith author Joyce Faulkner sits across from writer and UAFS Assistant Professor of History Tom Wing at the Fort Smith Library on Rogers Avenue. The two talk easily, sometimes finishing each other’s sentences. “We work really well together,” Joyce says, and Tom smiles. It’s been four years since the two began collaborating on the historical fiction novel Julia and Maud, based on a tryst that shook Fort Smith in the 1890s.

Joyce is responsible for the “fiction” in the novel, such as using a fictional narrator who reports on the misbehaviors of the real-life main characters. Tom is the writer who made sure the history and details were flawless.

“The story covers the rich period between 1894 and 1898, the events happening in the heyday of the Federal Court in Fort Smith,” Tom says. “You’ve got the execution of Lewis Holder [who vowed to come back as a ghost and haunt Judge Isaac Parker and the jury]. You’ve got Cherokee Bill trying to escape from the jail and killing a local guard. These notorious outlaws are in the backdrop of Julia and Maud’s story.

“Judge Parker is going to lose the jurisdiction of the court and die during this time period,” Tom adds. “The end of an era. It was a critical time in this city’s history.”

Together, they built a world of railcars and recklessness. Of misdeeds and miscreants. Much of the story unfolds in and around Garrison Avenue in downtown Fort Smith. The setting is detailed enough to make the reader feel the rumble of the train pulling into town, to hear the dark thunder rolling in from Oklahoma and across the Arkansas River.

It didn’t hurt that the main story had enough intrigue to build lasting momentum. When Fort Smith sat on the edge of the Indian Territory, there was a young woman named Maud Avery Allen. While she needed money, what she craved was attention, first from her husband and then from her married lover, Fagan Bourland. At twentysomething, thin and beautiful, she turned more than a few heads. Maud broke the rules of polite society. She swore like a heathen at a time when delicate speech was the height of femininity. She spoke of herself in the third person, “Maud wants you to buy her a fur-lined coat.” She set her sights on something that wasn’t hers and made sure she got it—come hell or high water.

In the mid-1890s, Maud was a scandal wrapped in a bustle, as Fagan and Julia Bourland were soon to learn. Both had strong opinions about this woman from Kansas. Julia, eyes wide open, saw her as a lethal threat. Fagan, it seems, saw Maud as a combination of wantonness and willingness, which made her irresistible to him.

Maud’s résumé is not one designed to get a crown in Heaven, and yet, both Joyce and Tom found enough in Maud’s circumstances to cause them to care. “We know that her sister died, and within six weeks, her father died. She was the oldest child, and her family was literally starving to death. It sounds as if her mother wasn’t well either. She had brothers. But Maud was the one who must put food on the table,” Joyce says. “Fagan had money, and she was desperate for it.”

One hundred and twenty-six years after her violent death, the people of Fort Smith are still talking about Maud’s trespasses. Her trial in 1896 was held in Judge Isaac C. Parker’s courtroom. Parker typically handled grimmer cases. Maud was a rare exception. She was charged with sending obscene materials through the U.S. Mail. The evidence showed foul and racist rants, complete with crude drawings, mailed to her lover’s wife.

Which brings us to Julia Bourland, someone Joyce calls complex but likable. It was seemingly Julia’s good fortune to marry Fagan in 1880. In Fort Smith, the pair was respected and envied. As time went by, they acquired a mercantile/saloon at 213 and 216 South Sixth Street. They owned the telephone company and a hotel on Garrison Avenue. When the Bourlands stepped out, it was in style. They had little to worry about. Three sons. Enough money to be comfortable. And life, as Ray Baker, a mayor in the distant future, would say, was worth living in Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Maud entered the Bourlands’ lives in 1894. At that time, Julia was thirty-three, and Fagan thirty-two. There has been much speculation about the Bourlands’ marriage. Why, for example, were there only three children in an era when many children were the norm? Could it have been a danger for Julia to carry another baby? And did this danger cause the Bourlands to reach an agreement? A kind of “don’t ask, don’t tell” arrangement that allowed Fagan to discreetly wander while Julia pretended not to notice?

Of course, it’s impossible to know. What we do know is that Julia loved Fagan until the day she died. And Fagan claimed to love Julia, although evidence of that love was often abysmal. After Julia died, Fagan donated money to First Methodist Church to construct a carillon in her honor. Fagan lived until 1952. The entire family is buried at Oak Cemetery in Fort Smith.

In 1897, the rivalry between Julia and Maud came to a ruinous end, although when you read Julia and Maud, you’ll see the writing on the wall long before then. It’s hard to imagine any other outcome, given the stakes and the hearts that were broken.

Tom, ever the historian, also believes this story is the creation of time and place, as well as personal choices. Both Julia and Maud were daughters of soldiers in the Civil War, which ended in 1865. One fought on each side. The women were likely raised with the effects of that war, at least how it related to the emotional damage done to their fathers. The world sat on the precipice of change, with the Puritanical Victorian era winding down. And Fort Smith, known for its Federal Court and the justice it meted out with an iron fist, had a wide-reaching reputation.

In a twist that is stranger than fiction, Fagan Bourland, long after the dust of the scandal settled, served four non-consecutive terms as Fort Smith’s mayor. An entire book could be written about Fagan, but Joyce and Tom say that book is not theirs to write. “We could have written a book about Fagan, but we wanted to tell about two women not many knew about,” Tom says.

“Both women will break your heart,” Joyce adds.

Tom touches his brow. There is something about him, something meticulous when it comes to detailing history. For him, the long-ago holds as much sway as the here-and-now. He loves finding evidence of things that were. Visceral artifacts that prove what really happened. He asks to read his favorite chapter in the book. He turns the pages until he finds the story of Cherokee Bill’s hanging, an event that was reported to have drawn approximately 3,000 witnesses.

Tom says of the passage, “I gave Joyce the factual narrative of that, and she took it and put it in the narrator’s voice. I tell you; I think it’s wonderful, down to the elm trees and the hanging being delayed for the train to arrive.”

Joyce beams. Her pleasure comes from forming characters from dust and fact, musing and mist. She has found solace in writing about Julia and Maud, in setting the record straight. She is proud of the job she and Tom have done. And both credit a host of people, listed at the back of the novel, who helped them unearth this story.

Is the story perfect? Neither author believes so, but it gets as close as historical fiction can. By all accounts, the Bourland family did much good for the City of Fort Smith, and so did their descendants, many of whom are still here today. For example, it was Fagan Bourland who was responsible for getting Garrison Avenue paved. He attended the dedication for the bridge that spans the Arkansas River between Fort Smith and Van Buren.

The novel also shows the complicated life of a young woman named Maud. A young woman who wanted to make a name for herself. Who wanted to be somebody. In a terrible way, she succeeded.

Julia and Maud is available at Bookish and the Fort Smith Museum of History in Fort Smith and at Chapters on Main in Van Buren.