Soul Food

Nate Walls stands before three large pans, a long-handled spoon in one hand and a clamshell foam plate in the other.

“Let me fix you a plate,” he says to the visitor, slicing the nose of the spoon into a well of Brussels sprouts and sweet potato. He won’t take no for an answer, even if you felt like objecting.

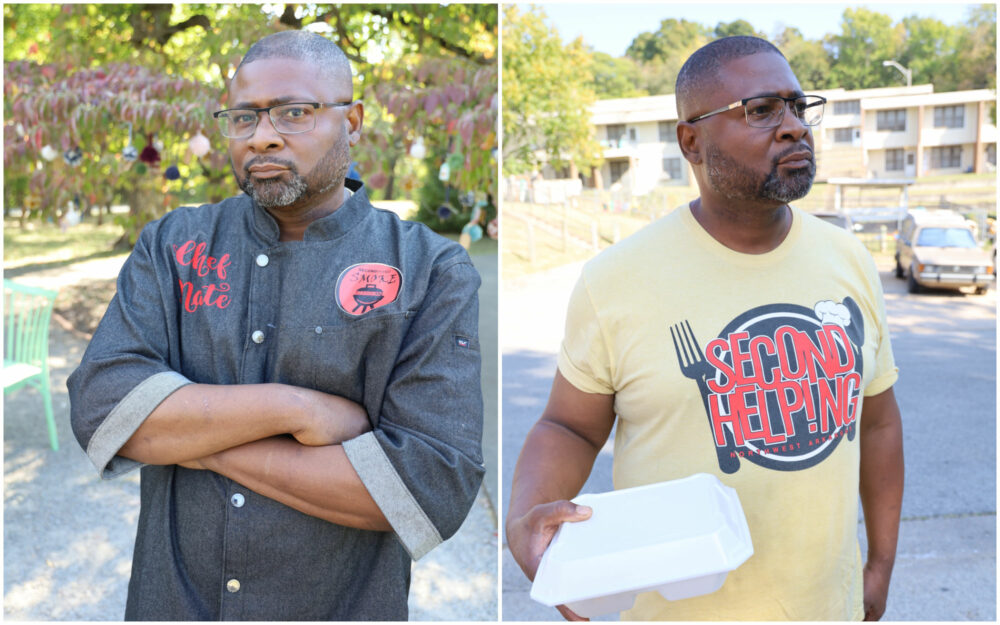

Chef Nate’s purpose in life is to feed people and feed them he does. Through his Fayetteville catering company, Second Hand Smoke, he pays the bills and through his nonprofit Second Helping, he pays it forward. It’s his way of lifting others and the communities they collectively embody, one spoonful at a time.

“You know, sometimes you think you’re the most important thing in the world and you’re not,” he says, the spoon now deftly ladling macaroni and cheese onto the plate. “The ability to do for somebody else just kind of changed my heart.”

The appearance and mannerism of the soft-spoken chef are shocking contradictions to what he tells you nonchalantly of his background. You can scarcely imagine him as he says he once was: addicted, directionless, headed inextricably toward jail or the grave. He talks about his past effortlessly and without bitterness; the way he sees it, what he’s lived through is a real-life calling card that’s so relatable to the people he serves, it loosens their own life stories, some for the very first time.

“When people eat, they talk,” he says, now plucking mahogany pork ribs from a nearby pan. “My mama used to say when everybody was arguing in the house, ‘Let’s just bring it to the table.’ We’d meet on Sunday and talk about all the stuff that happened that week. That’s why we call it breaking bread with people; just talking about things. It is intimate. People tend to tell you stuff over food that they wouldn’t typically tell you.”

Nate has watched food in all its wizardry since he was six years old, working in the kitchen of his adoptive mother’s juke joint outside Stuttgart. There was nothing about the fare then that you’d mistake for high cuisine, just the latest chapter in the legacy of the Delta, of taking what many reject and turning it into something everyone clamors for.

“My mom didn’t have much, and I learned so much coming up from people like that,” he says. “I think that’s kind of where my heart was. That’s how I embrace the compassion for the community and people who don’t have much today. I understand the side effects of poverty.”

By the time he was a teenager, the side effects of his situation had Nate in their grip – drinking, drugs, trouble. Even an intervening stint in the U.S. Army failed to provide the needed wake-up call.

“I went [into the service] because it was so disciplined and had so much structure which I didn’t know much about,” he says. “But I kind of pushed back on that and as soon as I got the green light, I was like, I’m ready to get out, you know?”

The Army did further his culinary skills and inspired him to at least attempt to advance his education at the University of Arkansas upon discharge. Formal schooling didn’t work out – too much distraction by women and partying, he says – and his problems with drugs accelerated him from user to dealer to statistic, a young Black man headed nose-first toward rock bottom.

“I was incarcerated and still didn’t understand what manhood was,” he says. “I got married and didn’t do well as a husband. I did really good as a father, because I didn’t have one. I wanted to excel at being a husband too, but I didn’t do very well.”

What Nate understands now that he didn’t know then was how deeply rooted his issues were in his difficult upbringing. His birth mother had struggled under addiction and domestic abuse, a reality that led her to put Nate into foster care. His adoptive mother took him out of the system, but her hardline tactics were hurtful to his self-esteem and sense of worth.

Today, Nate speaks of his mother in terms that are appreciative of what she did and forgiving of that which, for whatever reason, she could not do.

“She did the best she could, but she was limited in her education and understanding of how to handle certain things,” he says. “Not to say abuse is OK, but some people don’t have the resources to understand what that does to a child and how it affects their mental health. There’s such a stigma attached to that.”

Through it all, food was a central theme in Nate’s life and relationships, in ways both sorrowful and redemptive. When he left home, he says he proclaimed to his mother he would never cook again. When she died, his grief doubled down that promise, and he couldn’t bear touching a pan for fifteen years. When at last his marriage collapsed, it felt as if nothing of value remained.

“My rock bottom might not have looked like somebody else’s; I hadn’t lost my job, but I lost everything else,” he says. “My wife left. My brother died, we used to cook together a lot. That was my rock bottom.

“In the midst of that, I was trying to quit on my own, the drinking and stuff. By the time I finally went to AA, I went into a real dark place and I didn’t want to live anymore. My business partner now, she wouldn’t let me give up. She was going through cancer at the same time and so we were kind of commiserating. I was there for her cancer journey and my problems just kind of paled in comparison. I decided I never wanted to go back to where I was.”

Nate rededicated himself to cooking and launched his catering business Second Hand Smoke in 2017. He caught his big break after agreeing to cater an event for free, his food so impressing the guests they booked him for one paying gig after another. Everything was booming, right up to March 2020, when he came to the most fateful moment of his career.

“When COVID came, my business just hit the bottom,” he says. “So, I took whatever I had, which was like $1,000, and said whatever this feeds, that’s what we’re going to do. I bought canned goods – nothing fancy – and made good comfort food, mac and cheese, mashed potatoes, fried chicken, smoked chicken, ribs. Then I literally started knocking on doors.

“People started seeing what I was doing in the community. People who didn’t have much wanted to help, so they would give me canned goods while I was out there. People started donating. From there, it just took off.”

Nate formalized his door-to-door mission to feed the hungry as Second Helping NWA, a nonprofit to which he dedicates three days a week to cook, package and distribute meals in the community. Second Helping is buoyed by the generosity of Mount Sequoyah, a Fayetteville event space that provides Nate a commercial kitchen for his nonprofit work. Lately, he’s approaching various foundations in the hopes of landing funding to expand the program. He’s much more comfortable with poaching than politicking, but he’ll do what he has to do to continue the work for which he was created.

“I’ve learned so much about myself,” he says. “Just to be able to pour into other people what we’re about, you know what I’m saying?”

The to-go plate finished, Nate leads the visitor to Willow Heights, a clutch of beige apartments resting against a Fayetteville hillside. It’s a nondescript place and late into the weekday afternoon few people are milling about, but it is ground zero for Second Helping and its mission to serve, nourish and inspire. Nate’s face shows conflicting emotions as he scans the unblinking windows staring back at him. Places like this – in ways physical, spiritual and memorial – are a homecoming and the people who live here, all of them, his brothers and sisters.

“Last year we did a big Christmas and Thanksgiving for people, and they just absolutely loved that,” he says, handing over the weighty to-go box at last. “Fed them with a couple other vendors and just loved on people in the community. Telling kids that they can do it, you know, that they are smart, and they can navigate through this bad time right now. Just hugging on people, telling people it’s going to be all right. It’s better up ahead.”

Second Hand Smoke

384 Sunbridge Drive, Fayetteville, Arkansas

479.841.4098

secondhandsmokenwa.com

Second Helping NWA4

79.841.4098

secondhelpingnwa.com