Caesar Johnson left his warm apartment, making his way into the cold Chicago night. The Korean War veteran was headed for his work shift, as supervisor at the Campbell’s Soup factory. The ice and snow outside were common this far north, even three months into the new year, but the eight-degree first breath he took outside stung nonetheless.

Maybe it was that breath that caused him to look down, or maybe it was the snow that blew into his face that night. Whatever it was, it drew his eye to a package on the steps of the apartment building, wrapped in some sort of cloth. Caesar nudged the box with his shoe and when it nudged back, his breath again burned in his lungs, this time in shock.

Under the thin fabric, an infant writhed against the cold in a shoebox. Dazed, Caesar looked up and down the silent street, but darkness and the falling snow revealed nothing. Whoever had left the child was long gone and, left out here much longer, the child would be, too. He quickly returned to the apartment, woke up his wife, woke up the neighbors, called the police.

Chicago’s finest showed up a few hours later, made casual inquiries around the neighborhood. Nobody saw nothin’, was about as official as the reporting got. One of the officers tucked the box under his arm and out the door as his sidekick lent a parting word to the shaken Johnson family. “Thank you,” says the policeman. “You saved the kid’s life.”

They pulled from the curb, squad car pointed to the local orphanage, March 20, 1965.

*****

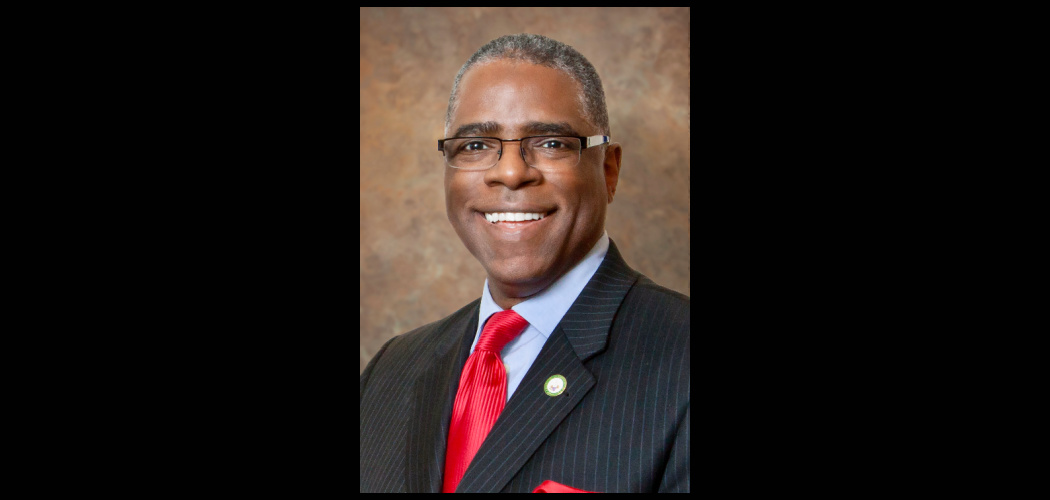

For a quarter century, Joseph Wood was well-recognized throughout Arkansas as a successful business executive, rising star in the Republican Party, Deputy Secretary of State and Washington County Judge. But as the saying goes, you never really know somebody and that applied to Wood himself. Adopted at age ten from what was then known as St. Vincent’s Infant Asylum in downtown Chicago, he’d felt the hole of unknowing as a part of his self-image for years.

“I grew up plagued with those thoughts,” Joseph says. “Those questions, especially in my teenage years, of why was I given away? I’m thinking it’s something I did that caused them to give me away. Well, what did I do?”

“The teenage years were probably the toughest. Getting into high school, you’re hanging out with your buddies and all and you don’t look like your siblings or you don’t act like your siblings. Then, my brothers and sisters, being brothers and sisters, we’d get into a fight, ‘Well, you’re not our real brother anyway!’ That’s just what kids do.”

His agonizing hunger for identity apart from the brood of Loretta, a teacher, and Sylvester, a construction worker, was just one of the opportunities Joseph Wood had to become a statistic. Another came when his parents split up and Joseph faced the same challenges of many single-parent households where he was expected to shoulder responsibility ahead of his time while resisting the call and pitfalls of rough Chicago neighborhoods like Rosemont and Jeffery Manor.

But there was something different about the teen of mysterious origin, named by orphanage-tending nuns. Blessed with exceptional leadership and organizational skills, Joseph poured his energy into his community, founding a youth club to provide himself and his peers a safe haven from drugs and gangs.

“Teens Together, it was called,” he says. “I remember it grew so fast and so big because many parents in the Jeffery Manor neighborhood were really trying to figure out where to take their kids to keep them safe and keep them from doing something destructive. The church gave me keys to the big fellowship hall and any time I needed to pull them together and meet, that’s what we did.”

“Next thing I know, I’m going to adult meetings as a teen liaison talking about what we’re seeing, what’s being heard out in the street, what other things [adults] can do to help support young people.”

Joseph’s questions over his origins didn’t fester any less for all his activity, but in time he reached a sort of uneasy peace with them, allowing him to move forward instead of being consumed by the riddle of his backstory.

“I spent a lot of time journaling and writing to God about it; was she too young, was she too old, was she a prostitute, was she in an interracial relationship that wasn’t acceptable, and they had to give me away?” he says. “After a couple months I’d let go of one scenario only to have another one pop up. Finally, the only way I could get through it is to get to a place where I’d say, ‘I guess it didn’t matter. She had me.’”

*****

Joseph graduated from Iowa State University and came home to constant frustration at the stagnant state of neighborhoods of color. “When I got out of college my mouth just hit the floor. I was really taken aback that so much of what I grew up in in Chicago was still happening with gangs and drugs,” he says. “I was so frustrated, I got involved in local school council, board elections. I mean, I got involved.”

In 1997, Joseph left for Arkansas and a job with Walmart where he’d ultimately retire in 2008 as head of international recruiting and staffing. From there, he went into full-blown public service as part of Secretary of State Mark Martin’s staff, overseeing ways for startup businesses to get off the ground more easily. He was also married and a father to two daughters by whom he felt the bonds of blood for the first time. But the old, nagging questions about his past, long dormant, would never fully settle.

“The laws changed in Illinois about eleven years ago saying if you were adopted, you can get your original birth certificate,” Joseph says. “I said, ‘Wow. If I get my original birth certificate, I can find out who my birth parents are. Then whatever happens, happens; I’m OK.’”

“When they finally sent mine to me, it was a foundling birth certificate. I never knew what that was. Never heard that term. I looked it up and it meant you were found, you were abandoned. Whoa! Just like that. It said you were found on this day, the day I celebrated my birthday, but no, that’s just the day I was found.”

Joseph may have been no closer to the motivations of his birth parents, but the discovery did reveal elements of his story previously unknown to him. The documents led him to Caesar Johnson, the man going to work through the snow of four decades past. Joseph made contact.

“Caesar was eighty years old then and he was flabbergasted, stunned. He was like, ‘Wow! You’re alive?’” Joseph says. “I’m bawling as I’m talking to him, I mean full-on, because this is the first time in forty-five years that I got any type of connection to where I came from. All I knew was I was adopted, that was it. Everything else was sealed to me.”

It’s funny how you find things when you’re not looking for them. Even as Joseph resigned the fact he will likely never know his birth parents, he now revels in new relationships. Caesar’s family refers to him as their little brother. As guest speaker at a gathering of orphanage alumni, a woman emerged from the audience and introduced herself as the former nun who named him. A woman calls from the West Coast, a former care worker at the orphanage. “You used to light up when you saw me and say, ‘There’s Mommy,’” she tells him.

As a public figure, first as Washington County Judge and now as a candidate for Lieutenant Governor, his story gets around, generating more calls from more people who fill in more gaps of his past. There’s talk of a screenplay about his life. The tale has even hopped oceans; as he was stunned to learn on an official visit to Africa.

“They threw me a birthday party,” he says. “They said on the continent of Africa, and in India, foundling is very prevalent. Most of them end up dying because they are left out to survive and many of them don’t. Those that do, many of them commit suicide by the time they are teenagers.”

“They told me, ‘For you to be where you are, we celebrate, because you are one of us.’ I just bawled; clearly this story resonates around the world. They see this all the time and to see one who made it through is worth celebrating. Because there is hope out there.”

Judge Joseph Wood

479.444.1700

washingtoncountyar.gov