[title subtitle=”words: Marla Cantrell

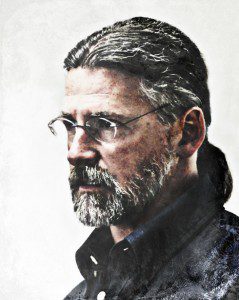

images:courtesy John Blase”][/title]

At four o’clock in the morning, the world has not quite opened her eyes. On the street, a lone driver traces her way back home after a long night at work. On the mountaintops, the trees of spring are the color of coal, their leaves as ruffled as petticoats. On the dark water of the mountain lake, nothing stirs, at least not on the surface. All that is alive and waking is down below, far beyond what we can see.

But at a kitchen table in Monument, Colorado, hours before he has to be at his day job, poet John Blase sits in a halo of artificial light. Nearby is his thesaurus, a treasure he keeps as close as his dearest friend. He reads his latest work aloud, and when a line doesn’t pull its weight, he opens the reference book, searching for its replacement. For John, the words are always auditioning, hoping to hit the pitch-perfect note that will allow them to stay.

Such is the life of this poet.

In March, in celebration of his fiftieth birthday, John released The Jubilee, his first book of poetry. The book’s cover shows a section of a white clapboard church, its gothic window the only adornment. The cover and the title say a lot about the author. Jubilee is a specially celebrated anniversary, typically the fiftieth. And the church encompasses most of who John is and the faith where his hope rests.

John started writing poetry six years ago as a counterbalance to his day job. As an acquisitions editor for WaterBrook & Multnomah, an imprint of Penguin Random House, he spends his days with books, typically 40,000 words or so in length, and at night all those words kept rushing in. So he’d take all those big manuscripts with big thoughts about faith and Christian living and winnow them down to a few lines of poetry, just for himself, an exercise in craft and utility.

Those poems needed a place to live, so John started his blog, A Beautiful Due. Soon, he had a substantial following. People who loved poetry were stopping by. But readers who hadn’t known they liked poetry at all were also intrigued. John’s poems about everyday life and everyday people had universal appeal.

Those poems needed a place to live, so John started his blog, A Beautiful Due. Soon, he had a substantial following. People who loved poetry were stopping by. But readers who hadn’t known they liked poetry at all were also intrigued. John’s poems about everyday life and everyday people had universal appeal.

Each line he writes is weighted with the divine, with his love for this temporal world, and for the world beyond that waits

for us when our time here is over. Not that he’s in any hurry to get there.

“I’m not a big fan of death,” John says. “I get it. I understand that life here ends. But I love this world, as messed up and as weird and oftentimes as painful as it is.”

At least in part, he owes that outlook to his parents, who handed him an idyllic childhood in the South. “My dad has been a Southern Baptist minister for over fifty years, with my mom working right beside him. Even though she wasn’t on the payroll, she did as much as he did, kind of in that ‘President and First Lady’ scenario. I have a brother, three years younger, who lives about an hour away from them in Southwest Arkansas.”

When he looks at the facts of his life—he’s a first-born preacher’s kid from the South, he says this. “That might be some therapist’s dream.”

John laughs, and then he tells the real story. “When I think back on my childhood, it was nostalgic in the best sense of the word. There were never any scandals in the churches my dad pastored, just a great life. I attended school for the most part in Texarkana, Texas, where I participated in sports and church. I was and am close to my brother.”

After high school, John attended Ouachita Baptist University in Arkadelphia. (His son is now a student there.) He’d planned on becoming a doctor, but after graduating, he decided to attend seminary, and eventually pastored churches in Arkansas and Texas.

He changed paths after fourteen years and now works with writers of faith, recently adding Eugene H. Peterson, the author of The Message: The Bible in Contemporary Language.

He credits his family and faith for his tender heart, and for his steadfastness. In June, he and his wife Meredith will celebrate their twenty-seventh anniversary. They have two daughters and one son, three children who fill him with pride and wonder.

In Colorado, his love of nature swells. The Rocky Mountains, Pikes Peak, The Garden of the Gods Park, all these places show the majesty of John’s western world.

Somehow, he is able to translate his feelings for the natural into his poetry. Last fall, when he thought about his upcoming fiftieth birthday, he decided to do something to commemorate it. He could run a marathon, he thought, but that would end the day the race was over. He wanted something permanent.

He gathered eighty poems, then sent them to his mother who offered to be part of the project, and they narrowed the field to fifty, one for each year of his life. He enlisted his brother, a graphic artist, who designed the book’s cover.

John does not expect to make so much money from his writing that his life changes much. When asked if someone can make a living from writing poetry, he smiles, considering. “I haven’t been able to,” he says. “But if you want to talk about making a life with poetry, that’s another story.

“Our words form us. Our words change us. As someone who believes in language the way I do, I’m always aware of that. And in this time of great division in our country, I, like so many other people, are paying attention to that.”

John pauses, and then he says, “Maybe in some way, I’m an evangelist of hope.”

The definition fits. John, who wakes in the morning so early not one bird has risen from its nest, sits at his kitchen table coaxing words into masterpieces. In his hands, the ordinary becomes immaculate and new. He has learned, as writer John Updike says, “to give the mundane its beautiful due.” And we are thankful that he has.

Below is excerpt from the Jubilee

I Don’t Believe I Ever Told You

John Blase

Are you ever afraid of dying?

I’m not talking about

the dying that will deposit you

directly into the Lord’s presence (as some hold).

But the dying that will tear

you from the fabric of here,

here where you’ve seen wonders.

I don’t believe I’ve ever told you I fear

that second kind of dying. But I do.

I’m telling you now because I’ve recently

seen how life changes in an ordinary instant,

reminds us we live in a game of gossip,

whispering our stories to the next in line.

We die. Then we’re passed along in

another’s tongue, and I’m afraid they’ll

edit a crucial detail.

For more on John, visit johndblase.com.

His new book of poetry, The Jubilee, is available at Amazon.com.