[title subtitle=”words and images: Jim Hattabaugh”][/title]

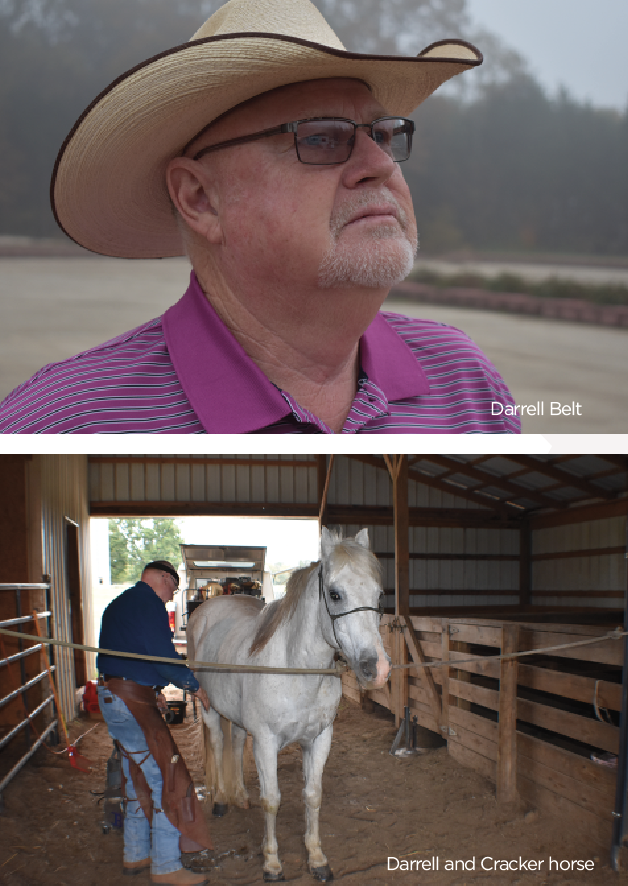

When farrier Darrell Belt was only fourteen years old, his father went blind from a burst blood vessel in his eye, which happened while he was shoeing a horse. While his father was able to regain some of his vision, he was not able to continue shoeing horses. Following this harrowing event, Darrell took over the horseshoeing business. It has provided a life-long career and a good living for his wife, daughter, and son, who is the third generation to enter the profession.

In the beginning, the horses were brought to the family farm in the Kibler bottoms to be shod. But since coming of age, he has driven the backroads of his home state of Arkansas, and Oklahoma, providing expert horseshoeing from his current home in Mulberry. Darrell, who carries several farrier licenses, says, “It can be a lonely job, but I enjoy my own company and even have an intelligent conversation every once in a while.” After forty-seven years in the trade, he also knows a thing or two about the danger of being close to horses.

In the beginning, the horses were brought to the family farm in the Kibler bottoms to be shod. But since coming of age, he has driven the backroads of his home state of Arkansas, and Oklahoma, providing expert horseshoeing from his current home in Mulberry. Darrell, who carries several farrier licenses, says, “It can be a lonely job, but I enjoy my own company and even have an intelligent conversation every once in a while.” After forty-seven years in the trade, he also knows a thing or two about the danger of being close to horses.

He has the broken bones, scars, and hospital stays to prove it. Yet, he has a passion for and love of working with horses. Once, a horse he was working on spooked and ran Darrell through a wooden fence. The exploratory surgery that followed showed a damaged spleen, liver, and lung.

Putting shoes on a 1,200-pound animal that may be as tall as he is—six-foot tall in stockinged feet—is hard physical work. He does most of his work bent over with a horse hoof between his knees. The horses don’t always want to cooperate. They can bite, kick and move very quickly so understanding horses and their behavior is imperative for their safety and his. Darrell says, “After many years, I can tell which horse may be an issue or is dangerous,” and takes the necessary precautions. Calm is good! Horses seem to sense if you are angry, frightened, or just having a bad day, and will respond accordingly. He has shod a horse while it was being held down on its side by the owners; otherwise, it was too dangerous. However, if he moves slowly, talks to these massive animals in a calm voice and places them where they feel safe, he can safely do his magic on their hooves.

Darrell’s days start early to avoid the extremes of weather and only end once he has nailed a shoe on the last horse. In the summer heat, he carries a fan to keep both him and the horse cool. “I prefer to work in the winter as there are not flies to pester the horse while I am working, and I can stay warm from moving,” Darrell says. He works six horses a day on average, five to six days a week, usually in a barn. If you multiply this number with the years he’s worked, that comes to almost 90,000 horses.

Darrell’s days start early to avoid the extremes of weather and only end once he has nailed a shoe on the last horse. In the summer heat, he carries a fan to keep both him and the horse cool. “I prefer to work in the winter as there are not flies to pester the horse while I am working, and I can stay warm from moving,” Darrell says. He works six horses a day on average, five to six days a week, usually in a barn. If you multiply this number with the years he’s worked, that comes to almost 90,000 horses.

On this particular misty day on a ranch in Porum, Oklahoma, he had six horses to work. Each is led to the breezeway of the big red barn. Darrell reaches up and strokes the neck and front leg of the first horse while speaking softly to her. The horse leans into Darrell as if to say, “Could I have those pretty Prada shoes on the back of the truck?” As he begins to work, it looks a lot like giving this gal a pedicure.

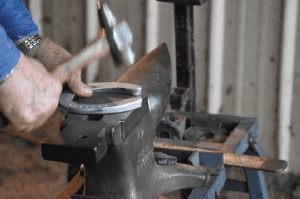

His method is the same in every barn. If the horse already has shoes on, the old shoes are removed, inspected for wear, and replaced if necessary. If the old shoe is still usable, it is reshaped to fit the trimmed hoof. If the shoe is new, the hoof is trimmed and prepped, then the shoe is fitted, shaped, and attached using horseshoe nails. The ends of these special nails are clipped and crimped to the hoof so the shoe will not come off before a final buffing and polishing take place.

Today, the first horse only needed a trim of her hooves, which involved cleaning out the bottom, snipping off the excess, much like clipping your nails, then smoothing and buffing the surface. And while her shoes were definitely not Prada, she seemed mighty proud of them.

Today, the first horse only needed a trim of her hooves, which involved cleaning out the bottom, snipping off the excess, much like clipping your nails, then smoothing and buffing the surface. And while her shoes were definitely not Prada, she seemed mighty proud of them.

Trimming, I learned, is the smelly part, and you have to watch where you step. Horses walk around all day in this stuff that stinks. Regular care of the hooves helps prevent infection.

Horses are also known to be flatulent. And that is evident in one of the horses that is standing nearby. This Cracker horse from Florida, bred to be stocky, strong and quick, has a gas problem that is piercing the air around me. The horse’s quickness is imperative, since this breed works with the Cracker cattle in the grasslands and swamps, tricky terrain to maneuver. On this day, catching the horse was a challenge, but once he quit running, it didn’t take long to replace his rear shoes, which are made of steel and come already forged, the most common type of horseshoes.

However, not every horse gets the steel shoes. One of the horses Darrell worked with today needed some additional help. She was pigeon-toed from having long legs as a colt. Darrell fitted her with orthotic shoes made of aluminum that seemed to have lifts on the inside to correct her knee issues. “Helping a horse with potential crippling conditions, or assisting an injured horse to get healthy is the best part of the job,” Darrell says.

The equipment he uses has improved through the years, and has become mobile, so a farrier can go to the horses, allowing the animals to stay in their comfort zone. I saw this for myself, when Darrell pulled his gas-powered forge, equipped with all the tools he needs, from his truck. The forge heats the shoes quickly so they can be hammered and shaped on an anvil.

As Darrell finishes up at this farm, he talks about his long career. He has worked on all types of horses. Rodeo and roping horses, barrel racers, and race horses. Roping horses wear special shoes on their back feet so they can slide to a stop without injury. He has also put shoes on mules and one bull. Both he and the bull were happy when it was over!

He views horses as athletes, every one as unique as a snowflake. “Each hoof on each horse is different; some need special shoes or a different size on each hoof,” Darrell explains. In some cases, he’d had to reshape one shoe as many as five times to get a fit that satisfied him.

There is a tried and true saying that goes, “Close doesn’t count except in horseshoes.” While this may be true of the game of horseshoes, it doesn’t translate to the actual shoeing of horses. In that endeavor, everything must be precise, no matter how long it takes, no matter how many fittings a horse requires.

As Darrell talks about that need for perfection, he reflects on how this all began, a fourteen-year-old boy intent on helping his father. Now, he sees how that troubling time led to a fulfilling career. Darrell says, “Kept me out of the factories. I can be my own boss, set my own schedule.” And even though he is of an age where many retire, his passion and love for what he does keeps him driving the back roads.

As I make my way home, I consider what an amazing experience it was to watch Darrell. He lays out his tools like the skilled artisan he is, then horse, man, and tools all work together. It was an incredible thing to watch.

It’s hard to imagine Darrell living a life without horses and horseshoes. He feels the same way. Being close to these animals has made all the difference in the world.