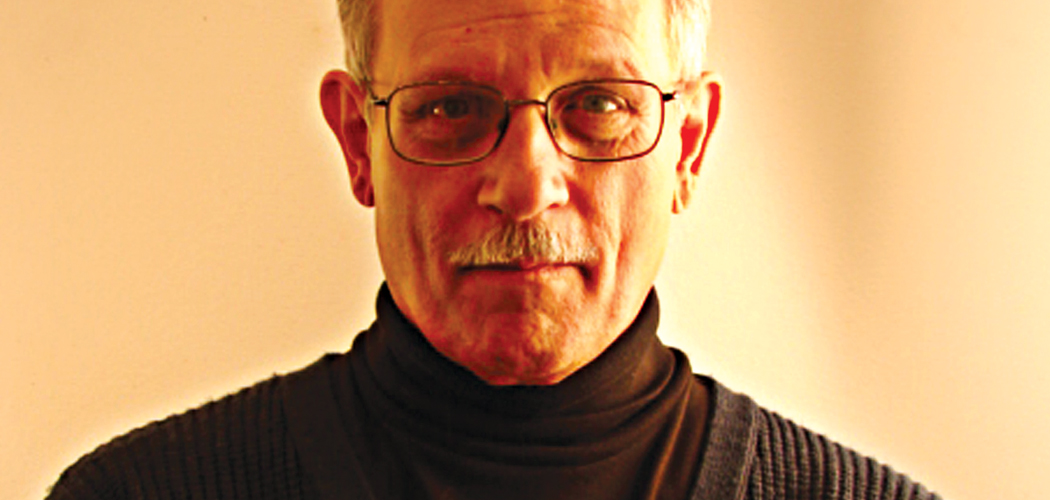

[title subtitle=”words: Anita Paddock

images: courtesy E.A. Allen”][/title]

E. A. Allen says his life as a CIA Intelligence Officer, historian, teacher, and writer began in the shadows of Saint Boniface Church and Elementary School in Fort Smith, Arkansas. “It was there I learned to read, write, and take a vigorous blow to the knuckles without showing too much emotion,” E.A., who’s sixty-six, says, when explaining the way the Benedictine nuns of that time disciplined kids like him. His parents, Kirby and Catherine, were devout Catholics and insisted their children attend Catholic schools, and they both worked hard while their children were watched over by an elderly aunt. “We had the run of the town from one side to the other. At that age, I thought Fort Smith was a wonderful place, and I really never had any desire to leave it.”

He also discovered Fort Smith’s Carnegie Library, the mansion that was never meant to be a library. It was there that he noticed what he likes to call “the hypnotic atmosphere of a great library.”

He enjoyed sitting at the long tables in the various rooms, reading his favorite histories and mysteries, two topics he says he, “wandered lazily into.”

E.A. was drafted during the Vietnam War. “My brother went into the Army and Vietnam, while I went to the Air Force and the Arctic. He nearly died of heat prostration, and I of succumbing to freezing temperatures.” Although he never thought of leaving Fort Smith, the military experience showed him that there was another world out there.

After his stint in the Air Force, he enrolled in Westark Community College (now University of Arkansas Fort Smith). “My academic record was so awful that I was lucky they accepted me. It was the making of me, and that is why I believe so strongly in community colleges because it gives those the opportunity for a chance. Westark gave me my start in academics, and I ended up studying at the Sorbonne, (The Paris-Sorbonne is one of the oldest and most prestigious universities in the world, dating back to the twelfth century.) which speaks volumes for where a community college can take you,” E.A. says.

He transferred to the College of the Ozarks (now University of the Ozarks) in Clarksville. In that small college experience he found an intimate learning environment in which he could thrive and graduated with a degree in history. It was there that he met his wife, Betsy.

After obtaining a PhD in Modern European History at Tulane University and studying in France, he intended to become a university professor, but he found himself unable to find a job because, at that time, there was an excess of college professors already working. He says he answered a recruitment offer that he had originally received while in the Air Force and joined the Central Intelligence Agency.

E.A. worked almost exclusively in Europe, working on issues he knew best, the politics of Western Europe. “In the Cold War Era the Soviet focus was everything. That was a particularly busy and energetic period in American intelligence work. The Reagan administration really put more resources and attention into the business, and I found myself in the middle of the swirl.”

Later in his career, he occupied himself with the issues of knitting Eastern European countries with the West and convincing countries to avoid the bloodbaths that had previously seemed inevitable. He also found himself in “the thick of the disintegration of Yugoslavia and the ethnic-cleansing in Bosnia.”

He served on the National Intelligence Council during the rise of greater freedom in the Soviet Union, the first Gulf War, and in President Clinton’s administration, and he often lectured at the Department of Foreign Services Institute.

He retired early because there were many other things he wanted to do. “I had lots of itches to scratch. I wanted to teach, raise cattle, be involved in historical preservation, and write,” E.A. says.

After returning to the United States, he taught at several universities, eventually settling in Northwest Arkansas where he and his wife both had relatives. Their son, Nathan, now lives on a farm that’s been in the family since 1836. He is the eighth generation to live on the land. E.A. and his wife are restoring one of the oldest houses in Arkansas, The John Tilley House, built in 1853 in Prairie Grove. It is on the National Register of Historic Places, and in 1999 E.A. received an award from the Historic Preservation Alliance of Arkansas.

He considered mystery writing on a whim, one that he didn’t know much about. “I had published scholarly texts, and I knew those were only read by academics in some obscure journal,” he says. E.A. drew upon his time spent in Paris for his first fiction book, taking to heart the quote from Hemingway: If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you.

“I set When Beggars Die, published in 2013 by High Hill Press, in the Victorian/Edwardian era. My main character, Gerard de Montclaire, is a French detective and his partner, the Englishman Fitz, tackle murder and intrigue.” Because E.A. was weaned on the mysteries of that era, he set out to spin a yarn that he could have fun with.

“I set When Beggars Die, published in 2013 by High Hill Press, in the Victorian/Edwardian era. My main character, Gerard de Montclaire, is a French detective and his partner, the Englishman Fitz, tackle murder and intrigue.” Because E.A. was weaned on the mysteries of that era, he set out to spin a yarn that he could have fun with.

He began to study, and he soon discovered there is a craft to writing. The first draft of his Montclaire mystery was awful, but he remembered Hemingway’s quote that first drafts were always lousy. “It took me a while,” he says. “But I finally learned enough to rework my draft and turn it into a manuscript that I could sell to an agent and then a publisher.”

Since the Paris he writes about is not the Paris he remembers, he uses reference books on the Edwardian era and guide books with maps and descriptions. He keeps a large map of Paris from 1905 on the wall of his studio, and he often refers to it. “So far, no one has written me that I’ve made a glaring mistake,” he says, so all that research must have paid off.

When asked what he did during his work for the CIA, he says he’ll write about that when the time comes. “But it hasn’t come yet,” he adds.

Writing mystery fiction has exposed him to many unexpected pleasures. “I find that nice people congregate around writing. I have never encountered a group of just plain nice people in any other walk of life.”

It’s a fitting chapter in E.A.’s exceptional life, back home in Arkansas, far from the City of Life, far away from his days in the CIA.

[separator type=”thin”]

For more on E.A. Allen, visit montclairemysteries.com